The Iranian Revolution of 1979 was one of the great democratic

events of the twentieth century. In terms of numbers alone, it was one of the

largest revolutions in contemporary history, with about 10% of the population

taking place.[1]

It put to an end over 2500 years of monarchical rule, and promised the

establishment of a revolutionary democratic republic. But the subsequent

theocratic counterrevolution with its brutal repression, continues to mystify

many, including Iranians themselves. Much of this mystification is deliberate;

both the theocratic regime and the scions of American imperialist foreign

policy derive their legitimacy from the obfuscation of the revolution’s

origins, and the true nature of the regime in Tehran. Those overly focused on

the regime’s theocratic characteristic miss what it aims to conceal; the

brutally exploitative rule of the Iranian bourgeoisie. However, those on the

left who completely dismiss the theocratic element in favor of total class

reductionism are also missing the big picture. The Iranian bourgeoisie did not

“choose” theocracy on a whim; the establishment of the Islamist regime was the

result of Iran’s 20th century political and economic development. What

follows is an explanation of how the Iranian bourgeoisie arrived at this point,

as well as its contemporary internal divisions, and what these mean for the

future of the revolutionary left in the country.

The Persian Constitutional Revolution of 1906 was one of the first

great revolutions of the twentieth century. At the time, the Iranian

bourgeoisie was weak, concentrated in the urban centers of the country, and

heavily dependent on the British Empire, which controlled Iran’s oil wealth,

and benefitted from unequal economic treaties. The majority of the country

remained under a moribund feudal rule, mired in corruption and poverty,

supporting a decadent aristocracy. During this period the first political

parties and societies were formed by the embryonic nationalist bourgeoisie,

which, taking inspiration from Europe, aimed to establish a constitutional and

democratic state, and liberation from foreign control over the economy. After

12,000 revolutionaries camped out in the gardens of the British Embassy,

Mozaffar ad-Din Shah Qajar agreed to allow the election of a parliament.[2] This parliament, elected

by universal male suffrage, declared itself a constituent assembly, and

promulgated a constitution. But the death of the Shah the following year led to

an attempted counter-revolution by the nobility with British and Russian

backing, culminating in the shelling of the parliament in 1908 by the Russian

army. In 1909, the revolutionaries re-took Tehran and re-established the

constitution.

This first democratic period was undermined by chronic

instability, and the weakness of the national bourgeoisie. Iran remained under

the foot of British imperialism and the collaborationist bourgeoisie. Mirza

Kuchik Khan, a veteran of the 1906 revolution, launched a new uprising in 1914

centered in Gilan Province, which aimed at a complete overthrow of the

monarchy, and the establishment of a secular and democratic republic. Backed by

the Soviets, he established in 1920 the Persian Socialist Soviet Republic. But

Khan’s refusal to enact more radical reforms led to a split between his faction

and the Persian Communist Party. Despite this, the revolutionaries were

prepared to march on Tehran and solidify their rule.[3]

Before we move on to the rule of Reza Pahlavi, it’s important

to note here the defining weakness of these early revolutionary movements. They

were not mass revolutionary movements. As already noted, Iran was still a

predominately feudal society. The bourgeois democratic revolution remained

impossible to complete in a society with such a small and fractured

bourgeoisie. And the proletariat, the class needed for the socialist

revolution, was even more barely existent. Furthermore, Iran was a highly

decentralized state, with a stratified peasantry. Any unity on that front would

have been difficult to achieve as well.

The British, frightened by the prospect of a socialist Iran,

convinced the leader of the Persian Cossack Brigade, Reza Pahlavi, to launch a

coup d’état, force the parliament to make him Prime Minister, and crush the

rebellion. Unable to overcome its internal divisions, the Republic’s forces

were crushed.[4]

Originally, Pahlavi had planned to establish a republic of his own, inspired by

the Turkish Republic of Mustafa Kemal Ataturk. A coalition between the

Socialist Party and the Revival Party won the 1923 elections, with the

Socialist Party supporting Pahlavi’s republican program.[5] However, the clergy and

the British convinced him to drop his plans for a republic and to crown himself

Shah instead.[6]

The reality was that Reza Pahlavi was a political hack; the new face for the

continued rule of the comprador bourgeoisie. He had no real guiding program and

ideology aside from whatever best served his backers. The Socialist Party which

had initially supported him, moved into opposition and found itself smashed by

his newly-established police state. While not a fascist himself, he did take

some inspiration from Mussolini’s regime; aping his militarism, personality

cult, and single-party rule. Most of his rule rested on a vague program of

modernization, nationalism, and anti-clericalism. What Pahlavi did manage to

accomplish was the modernization and centralization of the Iranian state, and

with this, the emergence of the Iranian working class. But this centralization

also fueled emergent ethnic conflict, and state repression of national

minorities such as Kurds, Azeris, and Arabs intensified under the guise of

Iranian nationalism. His aggressive anti-clericalism also served to alienate

the conservative and devoutly religious peasantry, which, suffering under the

yolk of landlords and feudal remnants, found itself susceptible to nascent

religious fundamentalism. Furthermore, while the national bourgeoisie began to

increase in numbers and strength, the comprador bourgeoisie remained in

control.

During the 1930s, Pahlavi increasingly allied his regime with

Nazi Germany, and a German political and economic presence was cultivated in

the country. With the outbreak of World War II, Pahlavi remained neutral, but

continued friendly relations with Nazi Germany. The UK and the Soviet Union

looked upon this relationship with concern; at risk were Iran’s oil fields and

allied supply lines. Under the pretext of expelling German nationals from Iran,

the UK and Soviet Union invaded Iran and deposed Reza Shah. They placed on the

throne his son Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, and ostensibly restored constitutional

democracy. The 1940s and early 1950s were marked by an increasing struggle

between the national and comprador bourgeoisie, and the rise of the communist

Tudeh Party. The conflict between the national and comprador bourgeoisie played

itself out in the electoral arena between the pro-British Prime Minister and the

independent nationalist Mohammad Mosaddegh. Around Mosaddegh convened a

coalition that would eventually become known as the National Front, the

political party of the national bourgeoisie; its inception was marked by the

unifying of the bourgeois democratic forces against ballot rigging and

electoral fraud committed by the comprador bourgeoisie.

The Tudeh, meanwhile, began to establish deep roots among urban

workers, and while it struggled to gain parliamentary representation, it was

able to effectively mobilize the working class. The Tudeh was a strong early

advocate of women’s rights, pushing for universal suffrage, increased social

rights, and paid maternity leave. Additionally, its armed wing, the Tudeh Party

Military Organization, which included military officers, struck fear into the

ruling classes, and after it attempted to assassinate Mohammad Reza Pahlavi in

1949, it was banned, and a widespread crackdown was launched against its

members.[7] Despite its ban, the Tudeh

continued to be a powerful force within Iranian society of the era. However,

the Tudeh found itself unable to put forward a cohesive and effective program. Its

one consistent goal was for the establishment of a republic, but it vacillated

between a liberal popular front strategy, including making overtures to

religious fundamentalists, and a more militant revolutionary strategy.

In 1952, the national bourgeoisie was catapulted to power when

the National Front won a landslide victory in elections. The National Front

appointed Mosaddegh as Prime Minister, and it appeared as if a new era of

democracy and prosperity were to be ushered in. Like his contemporaries Nehru

in India, and Nasser in Egypt, Mosaddegh was a staunch nationalist, who favored

a strong social democratic economy, secularism, and anti-imperialism. His

defining policy, and the one that ultimately drove him into direct

confrontation with the forces of imperialism was his nationalization of Iran’s

oil industry. Unlike these other rising nationalists throughout the third

world, Mosaddegh was never able to secure the support of a solid base. The

comprador bourgeoisie resented him, as did much of the royal and military

establishment. Though Mosaddegh was able to convince the parliament to grant

him emergency powers to carry out land reform, curbing the power of the

monarchy, and bringing the military under the control of the elected

government, he was both unwilling and unable to go all the way and smash the comprador

bourgeoisie and the monarchy.[8] What was needed was the

culmination of the national democratic revolution that had begun in 1906. And one

of the key players in making this happen was the Tudeh. The Tudeh, however,

never took a firm stance in support or against Mosaddegh; sometimes denouncing

him as an agent of imperialism, and at other times providing him with crucial

support. Though their armed wing had suppressed an attempted military coup

against Mosaddegh, he forcefully suppressed a TPMO demonstration demanding he

finally oust the Shah and declare a democratic republic. In response, the Tudeh

dissolved the TPMO; the next day Mosaddegh was overthrown in the British and

CIA-backed coup.[9]

With the return to power of the Shah, the national democratic bourgeoisie and

the Tudeh were thoroughly repressed, and Iran became a vassal of the United

States, a pawn of Cold War American imperialism.

What damned Mosaddegh and the Tudeh was the inability of both

to take the decisive steps necessary to secure the completion of the democratic

revolution. The Tudeh alone was not strong enough to take power and establish socialism

in Iran, but at the same time that was not even part of its program. It adhered

to the “Stalinist” conception of two-stage revolution, and was therefore unable

to create a program that could bridge its demands for democratic reform to the

ultimate goal of socialist revolution. Additionally, it denounced Mosaddegh

when it should have thrown its full support behind him until the democratic revolution

had been fully consolidated. Mosaddegh, on the other hand, as already stated,

was too much in thrall of parliamentary procedure and the formalities of

liberal democracy. He had the mass support of the Iranian people, and significant

factions of the military; to complete the revolution, he should have used his

emergency powers to suspend the 1906 constitution, dissolve parliament, oust

the monarchy, and establish a republic. Mosaddegh, the committed democrat,

needed to become a dictator, at least temporarily, in order to defend

democracy. This he did not do. What defined this era of Iranian politics was a

lack of decisiveness on the part of the revolutionary and democratic forces; the

forces of reaction were able to seize upon this infighting and take the

decisive step their enemies were unwilling to.

The Shah’s dictatorship that followed the overthrow of

Mosaddegh was surely one of the most corrupt, incompetent, and brutally repressive

of the twentieth century. Totally dependent on the United States and the CIA,

the Shah looked down upon the Iranian people with nothing but contempt. Though

he tried to present himself as a modernist and a nationalist, the people were

not fooled. When confronted about this contradiction in 1961, he said “When

Iranians learn to behave like Swedes, I will behave like the King of Sweden.”[10] In 1976, Amnesty

International said of the Shah’s Iran that it “highest rate of death penalties

in the world, no valid system of civilian courts and a history of torture which

is beyond belief. No country in the world has a worse record in human rights

than Iran.”[11]

His “White Revolution”, a massive plan of modernization was a disaster; seeking

to create a new base among the peasantry by breaking the power of the old feudal

landlords, he enacted sweeping land reform. Instead of winning him support,

this land reform created a mass of impoverished peasants and landless vagabond

workers, unable to secure a livelihood for themselves.[12] These peasants, devoutly

religious and conservative, continued to resent the attacks upon the religious

establishment and were increasingly becoming radicalized; they loathed the rule

of the corrupt and decadent comprador bourgeoisie. Lacking class consciousness,

and the ability to understand their desperate situation, these peasants continued

to be drawn to the flame of religious fundamentalism, thirsty for justice

against the secular establishment they perceived as being responsible for their

miseries.

Opposition to the Shah’s rule was diverse, ranging from the old

National Front to the liberal Islamist Freedom Party to the underground Tudeh.

But three new forces emerged in the 1960s that would be decisive players in the

coming revolution. The first were the Organization of Iranian People’s Fedai,

which launched a guerrilla war against the Shah’s regime. Led by the Marxist

revolutionary Bijan Jazani, the Fedai opposed the moribund policies of the

Tudeh, rebuking it for failing to ally with Mosaddegh, and toadying whatever

the current Moscow line was. The Fedai believed that the Iranian people had to

be stirred out of their traditional attitude of passivity, and to this end it

conducted armed attacks upon military and police targets, with the goal of rousing

the people to their feet. It was also against the Tudeh’s passive policy of

survival and reformism, openly calling for a socialist revolution and the

establishment of a workers’ democracy.[13] The second force was the

People’s Mujahedin of Iran, led by Massoud Rajavi. Inspired by the “red Shiism”

of philosopher Ali Shariati (think an Islamic variety of liberation theology),

they preached Islamic socialism and democratic revolution. The Mujahedin allied

themselves with the Fedai, fighting alongside them in the guerrilla and

propaganda war against the regime. However, the Mujahedin soon split between

its Islamic socialist wing and its Marxist wing, which later became the Maoist

party Peykar (League of Struggle for the Emancipation of the Working Class).

The third force was that of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. Contrary to apologist

accounts which present Khomeini as a democrat turned tyrant, he never hid his

theocratic ambitions. For Khomeini, the Shah’s sins were his westernization and

secularism. One of the key points of the White Revolution was that it allowed

non-Muslims to hold public office. Khomeini denounced it as an “attack on Islam”,

and openly denounced the Shah. After his arrest, riots broke out in support of

him. From exile in Paris, Khomeini continued to agitate against the Shah, but

in order to broaden his base, he made overtures to leftists and liberals.

The Iranian Revolution smashed the comprador bourgeoisie.

During and after the overthrow of the Shah, revolutionary workers’ councils

were established.[14] It appeared as if Iran

were heading towards a situation of dual power, and socialist revolution. But

there was to be no Iranian October. Khomeini, upon his return from France,

proved himself to be a master political manipulator; his anti-imperialist and

anti-capitalist overtures won support from much of the left, including the Tudeh

and elements of the Fedai. The Mujahedin, Peykar, and the Kurdish communist

parties opposed his establishment of the Islamic Republic, but the lack of

leftist unity doomed them to defeat. Initially, Khomeini respected the norms of

liberal democracy; free and fair parliamentary and presidential elections were

held in 1980. His Islamic Republican Party won a majority, but faced a

significant parliamentary opposition. Additionally, the president, Abolhassan

Banisadr, was a veteran human rights activist and democrat, and was opposed to

Khomeini’s moves towards a more religiously conservative system. The battle

lines were drawn in preparation for an ultimate confrontation.

With the comprador modernist bourgeoisie smashed, and the

revolutionary situation in flux, the national bourgeoisie found itself unable

to directly rule on its own. If the left were not smashed, eventually it would

regroup and finish the revolution. It is for this reason that the bourgeoisie

threw in its lot with Khomeini. Any move towards a genuine democratic system

would have resulted in a victory for the forces of the revolutionary left. In

classic Bonapartist fashion, Khomeini declared himself above class interest,

claiming to represent divine rule. Khomeini was a master politician and

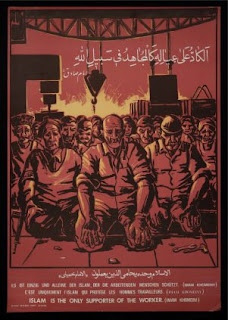

propagandist. The IRP made strong overtures to the workers’ movement, declaring

in propaganda posters that “Islam is the only supporter of the worker”[15], and organizing massive

May Day rallies. That other classic repository of reaction, the lumpenproletariat, also mobilized itself

in support of Khomeini; eager for wealth and power they formed the nucleus of

his Revolutionary Guard. The conservative peasantry finally got its revenge,

too. If the revolution was an urban affair, the counter-revolution was a rural

one. These desperate peasants, uneducated, illiterate, lacking class

consciousness, saw in Khomeini their savior who would deliver divine justice on

earth. At the height of the “revolutionary” religious fervor, Khomeini’s

supporters claimed to see his image in the moon. When Khomeini staged his coup

in 1981, ousting Banisadr, and banning all parties except for the IRP, the left

was mowed down by this coalition of reaction.

But the bourgeoisie, through its mullah interlocutors, didn’t

stop there. The invasion of Iran by Iraq served as both a rallying point and a

distraction. In order to hold on to power, the regime refused Saddam Hussein’s

initial peace offer, dragging the war out for almost the rest of the 1980s. One

of the most insidious crimes committed against the Iranian people was the

massive use by the regime of child soldiers, drawn from poor and working class

families, and tossed out onto the front lines. Kids as young as twelve, wearing

the “keys to paradise”, were sent into combat or used as minesweepers. It is

estimated that up to 100,000 child soldiers participated in the war, and their

deaths accounted for about 3% of the overall casualties.[16] What can this be called

other than a form of class genocide? The ruling class will sink to any barbaric

low to secure its rule, including sacrificing the most vulnerable members of

society.

The degradation of women is one of the most notorious aspects

of the counter-revolution. Iranian women had played a key role in the

revolution, and the left had strongly supported women’s liberation. The ruling

class, to re-establish its control over the means of reproduction, stripped

women of their social rights, and threw them back into the home. Recently,

Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei denounced gender equality as a western and Zionist

plot to undermine Islam, but let slip the true motivations behind the

repression of women; to ensure their continued role as housewives and mothers.[17] In the eyes of the

capitalists, women are nothing more than machines for producing new workers.

The restrictions on travel, employment, and education levied upon Iranian women

come from the same place that any restrictions and repression against women

come from; to ensure their continued reproductive exploitation. The imperialist

“human rights activists” miss this point; then again, imperialism only supports

women when they can be of use to its objectives.

Islamism was also used as the pretext to continue the repression

of ethnic minorities; in particular the Kurds and the Arabs. Iranian Kurdistan

has long been one of the centers of revolutionary socialism in Iran, and was

one of the main sites of armed resistance to the Islamic Republic in the years

after the revolution. To this day, a leftist insurgency continues there. In the

case of the Arabs of Khuzestan, their repression is more economic; Khuzestan

Province is one of Iran’s biggest oil-producing regions. Yet it remains

impoverished, underdeveloped, and tribal. Paranoid about separatism, the regime

keeps the Arab workers oppressed under the triple yolk of nationalist

chauvinism, theocracy, and capitalism.

Despite the regime’s anti-capitalist and “revolutionary”

rhetoric, Iran remains a capitalist state. The Islamic Republican Party was

polarized throughout the 1980s between the “left-wing” faction of Prime

Minister Mir-Hossein Mousavi, and the pro-capitalist free market faction of

then-President Khamenei. With the end of the war, the bourgeoisie was finally

able to cement its control by 1) the mass execution of Iranian leftists in

1988, and 2) the dissolution of the IRP, and the expulsion of the Mousavi

faction from the government. With the election of Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani as

President in 1989, neoliberal and free market “reforms” were introduced.[18] These policies continued

under his successor, Mohammad Khatami. That the west sees Rafsanjani and

Khatami as “reformers” it is because of their economic policies that favored the

market and some level of foreign investment. What separates the Islamic

Republic from previous regimes, though, is that it represents the national

bourgeoisie; Iranian capitalism is a capitalism that benefits Iranian

capitalists, not imperialist capitalists. The opposition of the United States

to the Islamic Republic, and the years it spent decrying and sanctioning Iran

over its alleged nuclear weapons program is a front for the real desire of the

forces of capitalist imperialism; the regaining of supremacy over Iran’s

resources and economy that it lost in 1979.

The presidency of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad marked a turning point in

the Islamic Republic, because it brought to power that section of the national

bourgeoisie that had come of age in the early years of the Islamic Republic,

and owed its success to the regime, but was also resentful of the regime. Ahmadinejad

was in frequent confrontation with the clerical leadership, and sought to

increase the powers of the elected government, especially the presidency, at

the expense of the clergy. His vice president, Esfandir Rahim Mashaei even

publicly stated that the era of Islamism in Iran was over.[19] This section of the

national bourgeoisie that supported Ahmadinejad also promoted Iranian

nationalism over Islamism, countering the propaganda spread by the clergy that

Iran’s cultural heritage is one of Satanic decadence. But why then did the

establishment support Ahmadinejad to the point that it rigged the 2009

elections against Mousavi? After two decades in the political wilderness,

Mousavi re-emerged, and turned against the Islamic Republic he had helped to

create. His 2009 platform was a call for sweeping political and economic

reform; the restoration of full political democracy, the dissolution of the “morality

police”, the removal of discriminatory laws against women, social democratic

economic policies including strengthening the welfare state, and a thorough

revision of the constitution. Of course we should not see his newfound love of

democracy and social equality as indicative of any kind of true ideological

conversion, but rather as an expression of opportunism. But it was more than

reformist enough to scare the conservative bourgeoisie. The mass protests that

followed, which culminated in calls for an end to the Islamic Republic were the

closest Iran has come to a revolutionary scenario since 1979. That the

Ahmadinejad camp allied with its clerical rivals should not be seen as a sign

that they are somehow Islamists, but rather as an expression of the class

dynamics at play in contemporary Iran. The alliance was a temporary one to

stave off the formation of a more left-leaning government.

The election of Hassan Rouhani in 2013 marked the return of

power to the Islamic capitalist camp. With the conclusion of the nuclear deal,

and the opening of foreign investment in Iran, attacks on the Iranian working

class and leftist opposition have intensified. Minimum wage increases are no

longer being chained to inflation as mandated by Iranian law[20], and leftist labor organizers

are facing increased repression, including two of Iran’s most prominent labor

activists Jafar Azimzadeh and Shapour Ehsani-Rad. Teacher’s union leader Esmail

Abadi was also sentenced to six-years in prison, and several of the union’s members

have fled into exile.[21] Under Rouhani, executions

of political prisoners continue to increase as well. Aside from American

neocons, who still froth at the mouth demanding regime change, the rest of the

western capitalist class has gone silent over Iran now that they’re free to do

business again. This only serves to show that the “concern” expressed over

human rights by imperialist states are nothing more than crocodile tears.

Finally, then, what is the future of Iran and the Iranian left?

For the former, there are two scenarios. The first is that having secured its

rule, the Iranian bourgeoisie finally consents to a democratic transition,

similar to what happened in Spain after the death of Franco. The second is

another revolution. What is inevitable is that the Islamic Republic’s days are

numbered. It has fulfilled its purpose; soon the Iranian bourgeoisie can rule

openly, without the need to hide beneath turbans. The Iranian left sadly

remains fractured. Until the mid-2000s, the Worker-communist Party of Iran

dominated the underground left, but after the death of its founder Mansoor

Hekmat in 2002, it fractured, and the resulting organizations spend almost as

much time attacking one another as they do the regime. What is desperately

needed is a united front of all of the leftist organizations and labor unions.

Such a united front would need a flexible program, able to respond to the

immediate conditions of Iranian society. In all cases, it would need to be able

to mobilize the masses, and be prepared to seize power when the opportunity

presents itself. Unlike the liberals and reformists, the left needs to unite

the struggle for socialism with the struggle against theocracy and the struggle

for democracy. The demands for political freedom, women’s liberation, minority

rights, and economic justice are inseparable. Additionally, the Iranian left

needs solidarity from the global communist movement. Fearful of aligning with

imperialism, many leftists shy away from criticism of the Islamic Republic, or

engage in bizarre apologetics. One bizarre article by Andre Vltchek even

declares Iran an “Islamic socialist” state![22] Iran is a country with a

rich revolutionary tradition; we must have confidence that our Iranian comrades

will be victorious in the end.

[1] Rosenfeld,

Everett (28 June 2011). "Muharram Protests in Iran, 1978". Time. Time

Inc. Retrieved 7 May 2015.

[2] Abrahamian, Ervand, Iran Between Two Revolutions by

Ervand Abrahamian, Princeton University Press, 1982, p.84

[3] Abrahamian,

Ervand, Iran Between Two Revolutions by Ervand Abrahamian, Princeton

University Press, 1982, p.116-7.

[4] Makki Hossein, The History of Twenty Years, Vol.2, Preparations

For Change of Monarchy (Mohammad-Ali Elmi Press, 1945), pp. 87–90, 358–451.

[5] Abrahamian,

Ervand, Iran Between Two Revolutions by Ervand Abrahamian, Princeton

University Press, 1982, p.132.

[6] Glenn E.

Curtis, Eric Hooglund (2008). "Iran: A Country Study". Government

Printing Office. p. 27.

[7] Abrahamian, Tortured Confessions, (1999) p.84

[8] Abrahamian (1982), p. 268–70.

[9] Behrooz writing in Mohammad Mosaddeq and the 1953 Coup

in Iran, Edited by Mark j. Gasiorowski and Malcolm Byrne, Syracuse

University Press, 2004, p.121

[10] America's Mission: The United States and the Worldwide

Struggle for Democracy in the Twentieth Century. Tony Smith. Princeton

Princeton University Press: p. 255

[11]

Blum, William. "Chapter 9: Iran

- 1953: Making It Safe for the King of Kings." Killing Hope: US Military

and CIA Interventions since World War II. London: Zed, 2014. N. pag. Print.

[12] Abrahamian 2008, pp. 139–140

[13] Greene, Doug Enaa. "Devotion

and Resistance: Bizhan Jazani and the Iranian Fedaii | Links International

Journal of Socialist Renewal." Links. Links International Journal

of Socialist Renewal's Vision, 30 Apr. 2015. Web. 13 July 2017.

[14] Saber, Mostafa. "The Working

Class in Iran: Some Background - Class Struggles from 1979-1989 - Mostafa

Saber." Libcom.org. N.p., 1990. Web. 13 July 2017.

[16] Schmitz, Cathryne

L.; Traver, Elizabeth KimJin; Larson, Desi, eds. (2004). Child Labor: A Global

View. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 120. ISBN 0313322775.

[17] Dearden, Lizzie. "Iran's

Supreme Leader Claims Gender Equality Is 'Zionist Plot' Aiming to Corrupt Role

of Women in Society." The Independent. Independent Digital News and

Media, 21 Mar. 2017. Web. 13 July 2017.

[18] Anoushiravan Enteshami

& Mahjoob Zweiri (2007). Iran and the rise of Neoconservatives, the

politics of Tehran's silent Revolution. I.B.Tauris. pp. 4–5.

[19] http://alef.ir/vdcjimex.uqehmzsffu.html?49665

[20] Ramezani, Alireza. "Raise in

Minimum Wage Not Enough for Iranian Workers." Al-Monitor. N.p., 18

Mar. 2014. Web. 14 July 2017.

[21] "Six-Year Prison Sentence

Against Teachers Union Leader Upheld After Pressure by Revolutionary

Guards." Center for Human Rights in Iran. N.p., 18 Oct. 2016. Web.

14 July 2017.

[22] Vltchek, Andre. "Iran Is

Standing!" Www.counterpunch.org. Counterpunch, 30 Mar. 2016. Web.

14 July 2017.